Fashion as Fantasy

Forty six years ago on December 2, 1975, Antonio and Juan’s first American group exhibition, Fashion as Fantasy, opened at the Rizzoli bookstore on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Curated by Federico Suro and his then brother-in-law and Rizzoli director Roberto Polo, the early Winter preview brought together some of the biggest names in art, culture, and fashion.

Propelled by the conceptual ethos brewing throughout the 1970s, Fashion as Fantasy, which opened with a black-tie fundraising event turned happening, was an early examination of the relationship between art and fashion and the fruits of its exchanges. Initially, Suro and Polo approached this intersection with decided concision, aiming to use just a few artists from each discipline. Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Marisol from the art world, and Yves Saint Laurent, Halston, and Valentino from fashion were among the first choices.

Cocktail party at Roberto & Rosa Polo’s apt with (from left): Cathy Paul, Federico Suro, model Virginia Hay, Charles James, Robert Polo, and Juan and Antonio. Photo by Greg Kitchen

The merging of art and fashion was Antonio and Juan’s area of expertise, and their broad network of friends and collaborators served as a guide for the exhibition curators. As described by Suro, “Antonio suggested we needed more people and gave us a long list of artists and designers he knew both in New York and Paris.” From there, the show expanded from ten, to fifty three participants, evolving into an immersive, dynamic show that heavily utilized installation and live models in lieu of traditional display methods.

Led by this spirit of collaboration, Suro and Polo invented as they went, allowing their many studio visits during the planning phase to inform the direction of the exhibition. With this freedom, works were submitted in an array of mediums including, but not limited to, original garments, photography, installation, illustration, and projection.

In addition to their curatorial support, Antonio and Juan created the exhibition poster which visually captures the blending of art and fashion with an abstracted composition of stylized brushstrokes among disembodied eyes and lips. The artist’s names are drawn in small print throughout the page, melding the list of artists and designers as a part of the work itself.

Antonio was also one of the contributing artists. For his submission he created a grid of SX 70 Polaroids and Kodak Instamatics. In a deliberate departure from the fashion illustration for which he and Juan were known, Antonio instead used photography as a conceptual medium. Throughout the exhibitions’ two month run, he continually added works to his wall installation.

Fashion as Fantasy exhibition poster by Antonio and Juan

While explorations of fashion and art’s convergence are now commonplace within galleries and museums, in 1975 this idea was still a novelty. Leading up to this point, fashion exhibitions skewed antiquarian, so to frame fashion in relation to contemporary art was an attempt to frame these two dissonant subjects as intrinsically related, and to bring them into the present day.

Diana Vreeland had been named Special Consultant to the Costume Institute only two years prior in 1973, and her penchant for exhibition drama and style is often credited as a catalyst that expanded the field of costume to engage a wider audience. It was this same ethos of virtuosity that Suro and Polo tapped into during the conception of Fashion as Fantasy. Suro and Polo, however, not only applied this immersive quality of exhibiting fashion promoted contemporaneously by the Met, but took this a step further by borrowing installation techniques from the contemporary art world.

Renowned for his avant-garde window displays for Henri Bendel, Robert Currie was brought in to mount the exhibition. With Currie’s input, the scenography of the exhibition moved beyond the bookshop’s gallery space. Works were nestled between bookshelves, suspended from the ceiling, or, in the case of Diane von Furstenberg’s wrap dress, garments were tacked directly to the wall.

A New York Times Review of the piece published two days following the opening event sums up its chaotic experimental nature.

Fashion Meets Fantasy

by Bernadine Morris

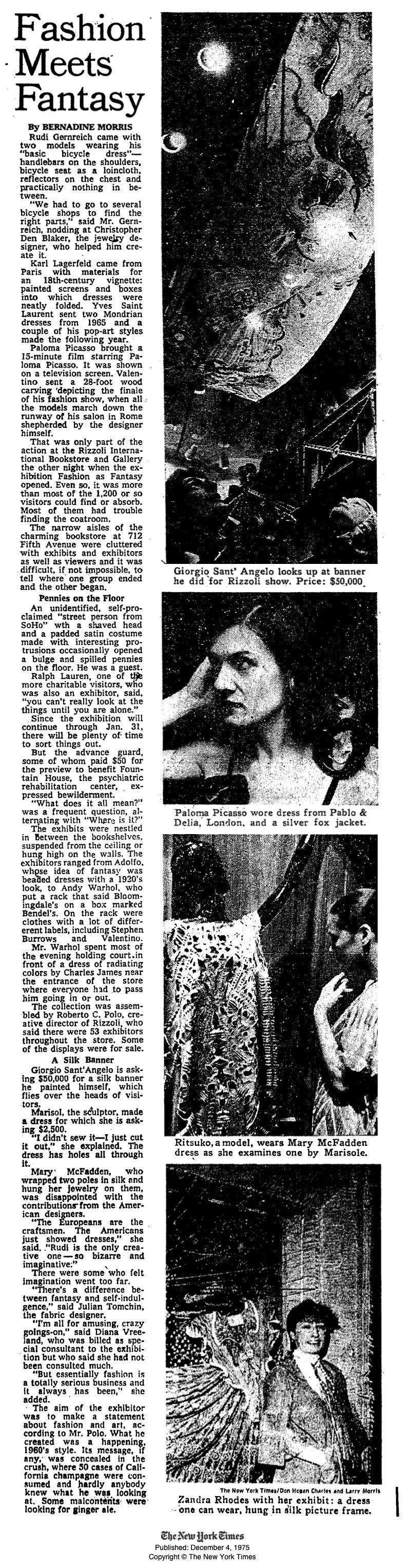

Rudi Gernreich came with two models wearing his “basic bicycle dress”—handlebars on the shoulders, bicycle seat as a loincloth, reflectors on the chest and practically nothing in between.

“We had to go to several bicycle shops to find the right parts,” said Mr. Gernreich, nodding at Christopher Den Blaker, the jewelry designer, who helped him create it.

Karl Lagerfeld came from Paris with materials for an 18th‐century vignette: painted screens and boxes into which dresses were neatly folded. Yves Saint Laurent sent two Mondrian dresses from 1965 and a couple of his pop‐art styles made the following year.

Paloma Picasso brought a 15‐minute film starring Paloma Picasso. It was shown on a television screen. Valentino sent a 28‐foot wood carving ‘depicting the finale of his fashion show, when all the models march down the runway of his salon in Rome shepherded by the designer himself.

That was only part of the action at the Rizzoli International Bookstore and Gallery the other night when the exhibition Fashion as Fantasy opened. Even so, it was more than most of the 1,200 or so visitors could find or absorb. Most of them had trouble finding the coatroom.

The narrow aisles of the charming bookstore at 712 Fifth Avenue were cluttered with exhibits and exhibitors as well as viewers and it was difficult, if not impossible, to tell where‐ one group ended and the other began.

An unidentified, self‐proclaimed “street person from SoHo” wth a shaved head and a padded satin costume made with interesting protrusions occasionally opened a bulge and spilled pennies on the floor. He was a guest.

Ralph Lauren, one of the more charitable visitors, who was also an exhibitor, said, “you can't really look at the things until you are alone.”… “What does it all mean?” was a frequent question, alternating with “Where is it?”

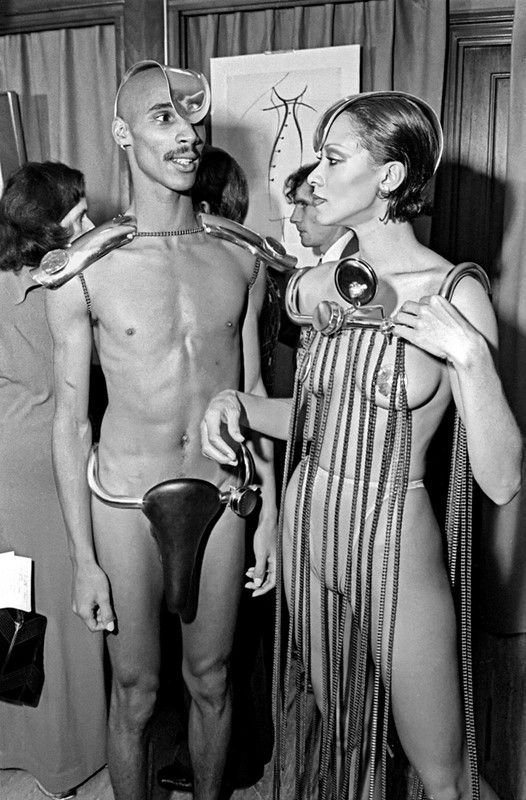

The exhibits were nestled in between the bookshelves, suspended from the ceiling or hung high on the walls. The exhibitors ranged from Adolfo, whose idea of fantasy was heated dresses with a 1920's look, to Andy Warhol, who put a rack that said Bloomingdale's on a box marked Bendel's. On the rack were clothes with a lot of differerent labels, including Stephen Burrows and Valentino.

Mr. Warhol spent most of the evening holding court in front of a dress of radiating colors by Charles James near the entrance of the store where everyone had to pass him going in or out.

The collection was assembled by Roberto C. Polo, creative director of Rizzoli, who said there were 53 exhibitors throughout the store. Some of the displays were for sale.

Giorgio Sant'Angelo is asking $50,000 for a silk banner he painted himself, which flies over the heads of visitors. Marisol, the sculptor, made a dress for which she is asking $2,500. “I didn't sew it—I just cut it out,” she explained. The dress has holes all through it. Mary McFadden, who wrapped two poles in silk and hung her jewelry on them, was disappointed with the contributions from the American designers.

While the exhibition’s avant garde nature proved difficult for the press, Fashion as Fantasy undoubtably served as a major turning point for the bustling post-modern 1970s. Deborah Turbeville, then in the early stage of her career, created an antifashion magazine titled “Maquillage.” Within its pages, Turbeville’s signature haunted, oneiric photography is paired with handwritten notes from her models describing the severity of life in New York. Although only one thousand copies were produced, the publication went on to be published by The Paris Review in 1977, and would later end up in the hands of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, leading her to commission Turbeville for her iconic Versailles images.

Excerpts from Deborah Turbeville’s Maquillage

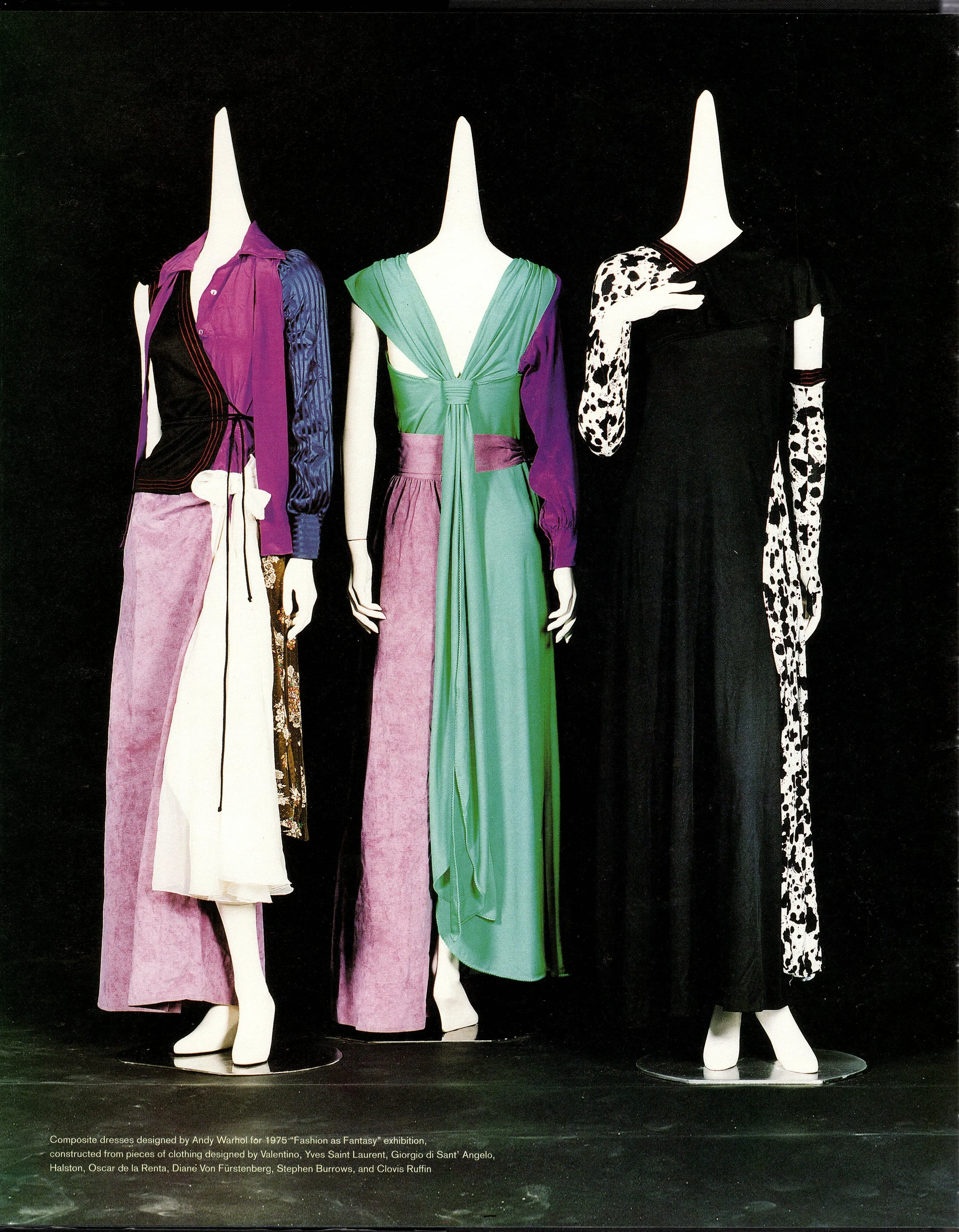

Composite dresses designed by Andy Warhol constructed from pieces of clothing designed by Valentino, Yves Saint Laurent, Giorgio di Dant’Angelo, Halston, Oscar de la Renta, Divane von Furstenberg, Stephen Burrows, and Clovis Ruffin. Photo from The Warhol Look

For one of his submissions, Andy Warhol created three dresses, each a collage of readymade pieces from the collections of Valentino, Yves Saint Laurent, Giorgio di Sant’Angelo, Halston, Oscar de la Renta, Diane von Furstenberg, Stephen Burrows, and Clovis Ruffin. The labels from the original clothing remained visible, aligning with Warhol’s Pop sensibilities that glamorized consumerism and commodities. This concept can be seen as a precursor to the work of Martin Margiela, who showed similar patchworked readymade garments in the 1990s.

Though Suro noted Andy Warhol regarded the show as “the greatest thing to happen in New York since the Armory Show,” Fashion as Fantasy was received with mixed reviews. Part of this confusion was due to many press outlets sending society reporters rather than arts and culture critics. Nevertheless, the exhibition championed the notion that fashion and art can work in tandem. As participating designer Zandra Rhodes’ told WWD when discussing her inclusion in an exhibition, “I believe my clothes are works of art.”

Written by Mary Kate Farley