New York, Paris — and Tokyo!

While the story of Antonio and Juan’s career is often focused on their connection to the streets and styles of New York and Paris, it would be a mistake to not recognize the huge influence and impact Tokyo had on the duo’s work from the early 1970s until the end of their lives.

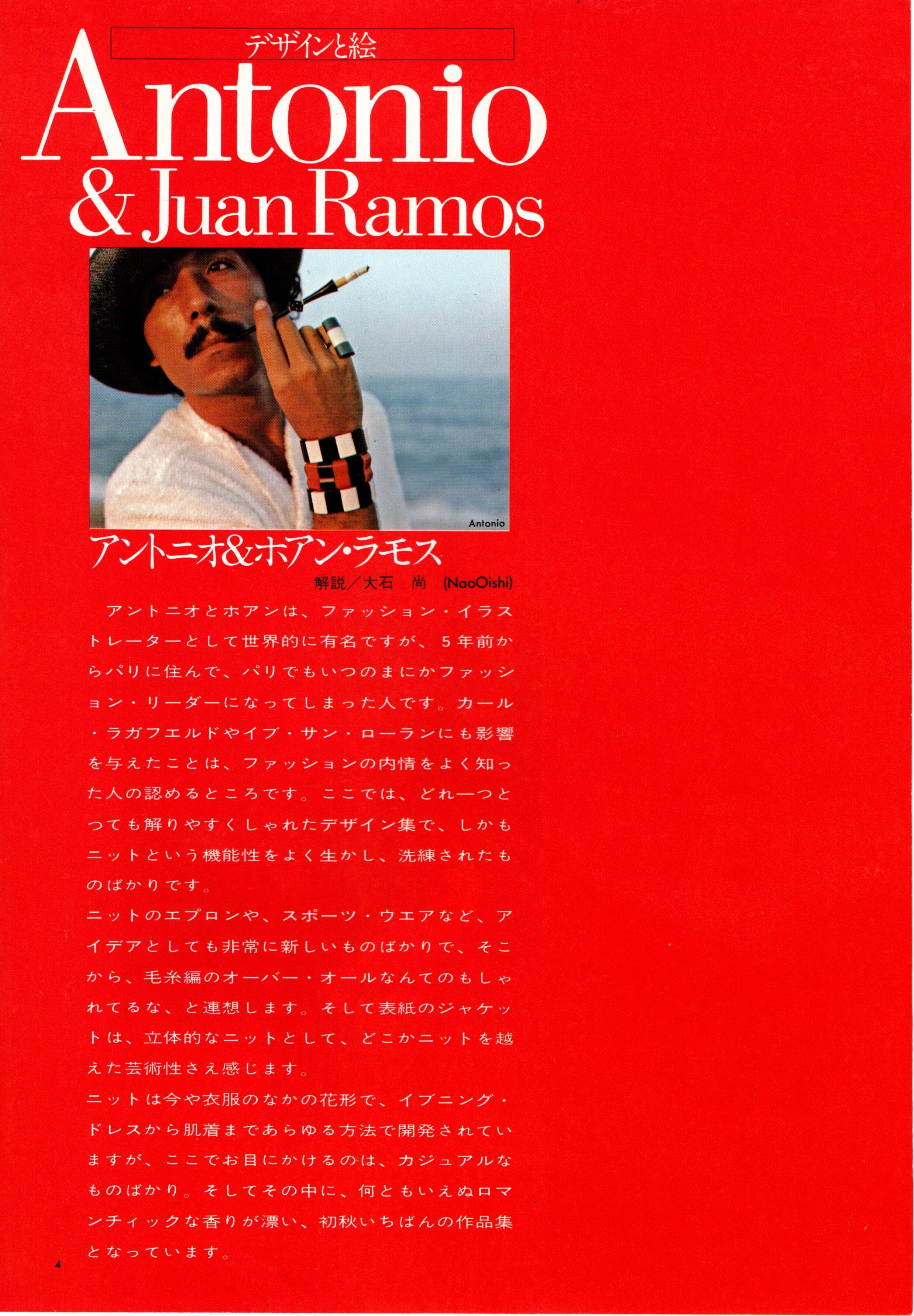

After having gained notable success in New York for their prolific illustration work, Antonio and Juan were introduced to Charles Manzo in the late 1960s. Charles was an American curator and art agent who was based in Tokyo with his wife, Nao Oishi, a writer and fashion reporter. The couple invited Antonio and Juan to visit them in 1969 and the synergy was instant. Charles quickly began working as their Asia agent, brokering commercial, editorial and advertising projects, in addition to organizing exhibitions and lecture seminars for the young artists. What flourished was a 15+ year relationship — and for the remainder of their lifetimes, Antonio and Juan would visit Japan regularly, bringing models from America and Paris to Tokyo and working out of make shift hotel room studios.

Antonio working from a hotel room in Japan, 1969

Antonio and Juan in Tokyo, 1969

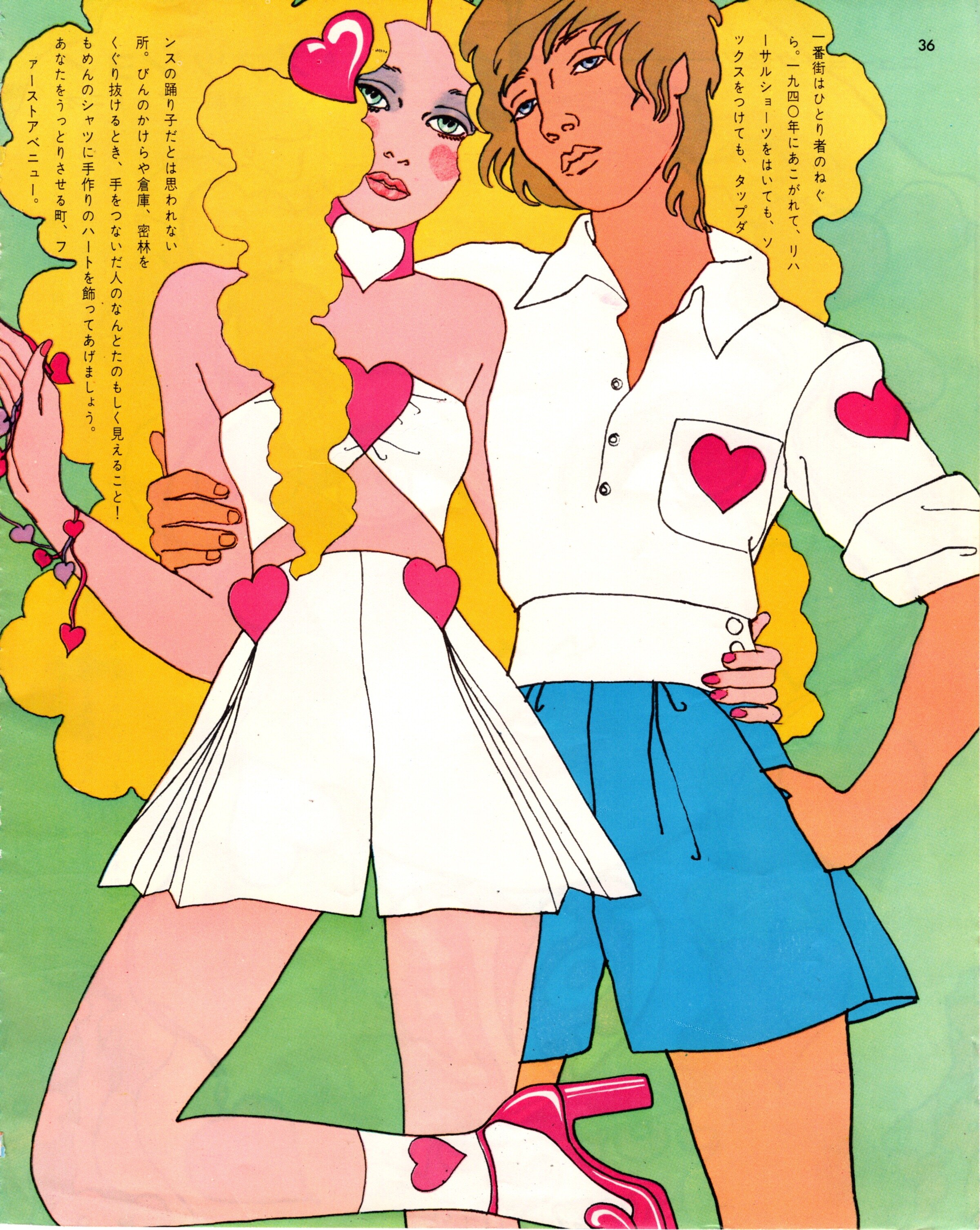

From the early 1970s onwards, Antonio’s drawings began appearing regularly in Japanese publications, including Asahi Graph, Soen Magazine, Playboy, and Vogue Nihon. Their reputation as "New York artists "and the pop, graphic style that he and Juan were exploring at that moment dovetailed with the Americana frenzy that had swept the country in the 60s, catapulting them to instant success.

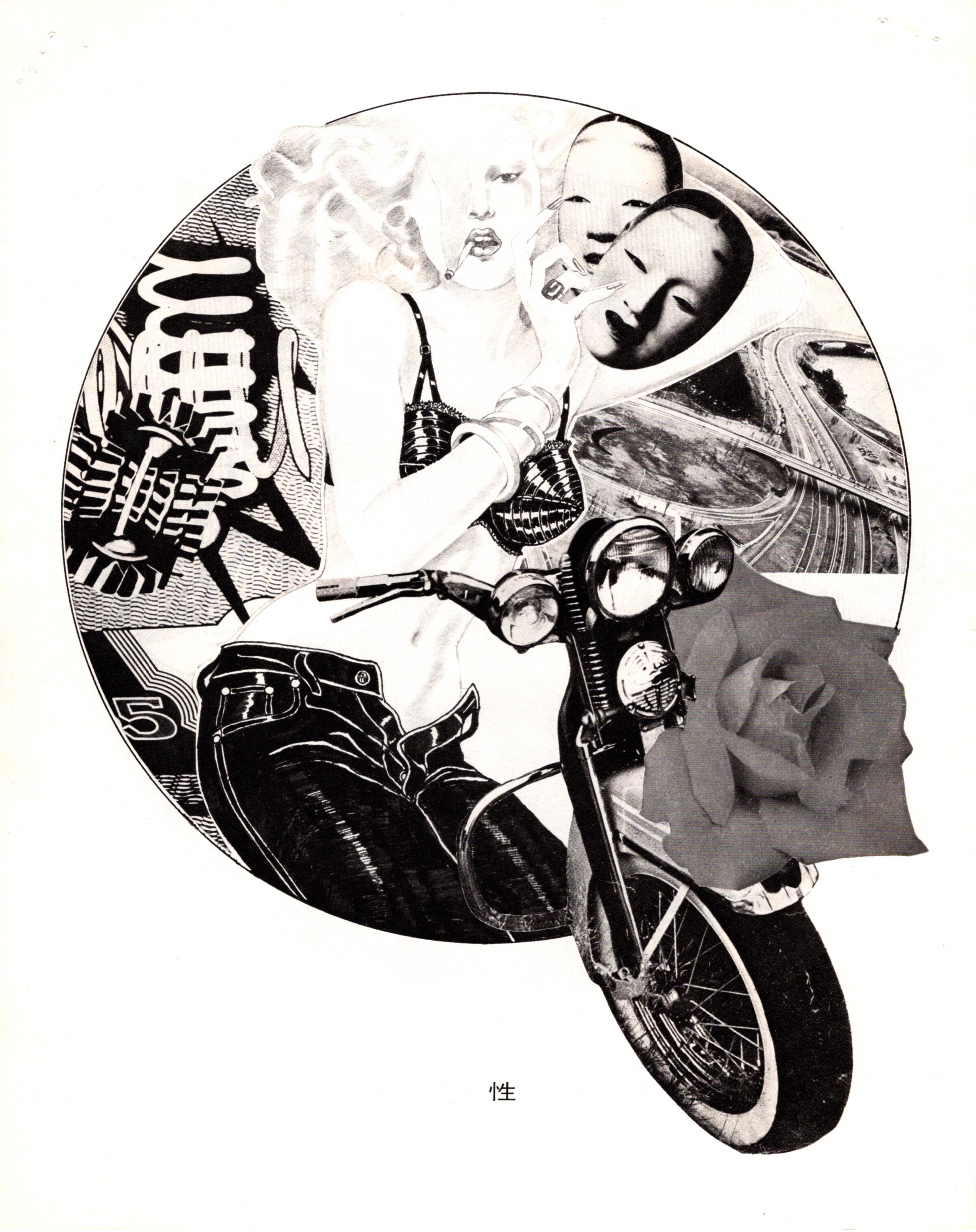

They also incorporated traditional Japanese styles into their editorial work, often borrowing techniques from Ukiyo-e, a classic genre of Japanese art from the Edo period known for its woodblock prints. The common motifs of stylized female portraits, Kabuki, folk tales, landscapes, flora/fauna, and erotica became strong sources of inspiration for the pair as they merged these styles with contemporary fashion.

Unlike the US or Europe, in Japan illustration was widely accepted as fine art, and Charles astutely positioned Antonio and Juan’s work in a gallery context parallel to their editorial emergence. They were able to have their first solo show at D.I.C. Gallery in Nihonbashi, Tokyo in 1970 (five years before they participated in a gallery show in their hometown New York!). In the decade to follow, A & J had 7 more solo presentations at museums in Tokyo and Kyoto, including at Matsuya Gallery, Odakyu Gallery, LaForet museum, Wako Gallery Hall, Bunka Fashion College Museum, The American Center, and Seibu Gallery.

Concurrent to the exhibitions, Antonio and Juan would host multi-day seminars for students at prestigious universities such as the Bunka Fashion College and Kuwasawa Art College, where they would host lively drawing sessions and give lectures on the history of fashion illustration.

In the late 70s - early 80s, their focus shifted from editorial to commercial work and product lines. They created advertisements for pioneering department stores Daimaru and Laforet, and iconic Japanese heritage brands such as Shiseido and Suntory Beer. As their popularity grew, “Antonio Lopez” as a brand name began to gain traction, and Charles brokered collection deals with the lingerie company Wacoal for a line of underwear and packaging bearing his name, as well as an independent “Antonio Lopez” textile and scarf line.

Suntory Beer

A 1977 advertisement for Suntory Beer featuring Jerry Hall as an anthropomorphized bottle. Back in New York, Antonio and Juan were experimenting with their “ribbon series” photographs, which served as inspiration for both the concept and typography treatment of this work.

Laforet

In 1978, A & J created the inaugural campaign for Laforet, which had just opened its modern six story building located in the mecca of Japanese fashion and culture, Harajuku. This iconic store quickly became a beacon for youth fashion, housing over 120 stores with established and avant garde designers, as well as an exhibition space. Antonio and Juan designed a 5 season campaign (spring, summer, autumn, winter, and Christmas). Four of the drawings were inspired by Renaissance painters Sandro Botticilli and Giambattista Tiepolo, with highly detailed photorealistic renderings that replicated the colors and dynamism of nature with a classical full frontal flatness to the figures. The fifth drawings took inspiration for the German Bauhaus movement, riffing on Oskar Schlemmer's "The Triadic Ballet."

Antonio Lopez Scarves

In the late 1970s, after having achieved success throughout Japan, Antonio was commissioned to create a line of scarves bearing his signature.

The vibrantly patterned textiles took inspiration from art deco with bold lines, sweeping curves, geometric forms, and a nostalgic nod towards the celebration of the industrial age. Pictured here are two gouache studies.

Shiseido

Two pages from “The Antonio Artist’s Palette,” a range of custom color shades inspired by a curated list of influential 20th century artists, presented to Japanese cosmetics brand Shiseido in 1977.

From the presentation it reads, “ The proper use of make-up is an art in itself. We help all who use make-up become an artist by supplying them with palettes using color schemes of different artists, including Antonio’s.. The person who uses this make-up not only becomes an artist, but can achieve the “look” an any artist she chooses.

Wacoal

The “Antonio Lopez” line for Wacoal was produced in the late 1970s and included a range of bras and underwear constructed for a variety of women’s shapes.

The corresponding ad campaign featured a woman rising from a lily, a flower most commonly associated with purity and fertility.

Antonio created a scripted AL logo that was featured prominently on the underwear, and later designed for Wacoal a series of bath robes, pajamas, and house clothes adorned with his initials.

In Tokyo in the early 1970s Antonio met sisters Adelle Lutz and Tina Chow (né Tina Lutz — Antonio would later introduce Tina to Michael and he and Juan would be witnesses at their wedding). Half American and half Japanese, she became one of the most iconic “Antonio Girls,” embodying a unique beauty that was both glamorous and androgynous.

Designer Kansai Yamamoto, model Sayoko Yamaguchi, and Antonio, New York City, c. 1980

Tina Chow wearing Fortuny, London, c. 1975

The opportunity to tap into the Japanese market was due in part to the burgeoning travel industry which allowed A & J to move quickly and effortlessly between New York, Paris, and Tokyo. Likewise, a host of seminal Japanese designers were living and working in Paris and New York at that same time, including Kenzo Takada, Issey Miyake, and Kansai Yamamoto, each of whom became friends and colleagues with Antonio & Juan.

This transient lifestyle opened up a world of cross-cultural exchange. People brought with them waves of fresh ideas, local fashions, and art movements. What made Antonio and Juan’s body of work so remarkable was their uncanny ability to synthesize it all - the old, the new, the foreign, the familiar — into something that was unequivocally unique wherever it was seen.